By Isma Ahmed

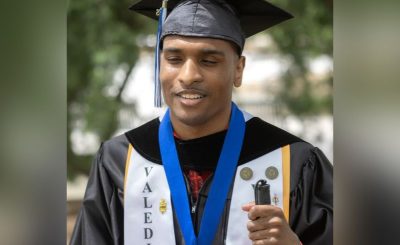

Last week I had the privilege of interviewing an extraordinary human and member of our faculty, Dr. Clarence Jefferson Hall. Professor Hall is from the vast upstate lands of the Adirondacks and has been teaching history at Queensborough since 2016. At Queensborough, he is an assistant professor in the Department of History. He leads the US History (survey course) courses, Recent American Civilization, History of New York, and Environmental History of North America. Dr. Hall is also a visiting professor of Sustainability Studies at Pratt Institute and has taught at other institutions such as Stony Brook and Binghamton University. In this interview, Dr. Hall embarked upon his works as an educator and an environmentalist and how his life and personal struggles have paved the way for all his professional and personal achievements. Professor Hall also discusses mental health, his research work, and methods on how others can benefit their environment.

How did being from upstate New York impact your fascination with history?

“Where I am from, there are many historic sites…history is always there. My mother worked as a secretary in the history department at the local state university, and I used to hang out at her office. I used to sit in college-level history classes in elementary school, and I hung out with the professors. They would give me the books they didn’t want. So, from an early age, I was just really interested in history.

And also, on a personal note, my home life was not fantastic, and it was an escape for me. It was real, but it was still like an escape. I could just get a free book from one of those professors, take it, read it, and go away from real life for a while. I liked seeing the professors teaching when I was young. I was like, ‘this looks like a fun thing to do,’ so I worked toward it”.

How did where you’re from influence you to teach history, particularly the history of New York State?

“Similar to what I said before, just the large number of historic sites being right there. That’s part of it. And, the work I did for my doctoral dissertation, my book, about that area. It came from a desire to know more about my dad’s experience. My dad worked as a state prison corrections officer, and he and I had a troubled relationship for several reasons. I was always interested in the world he inhabited of the prison system. So, I just wanted to use that research opportunity to learn more about it. He talked about it, but it was here and there. He’d mention things. I didn’t have a full picture, and so that kind of interested me in focusing on New York because I was, and still am, very intrigued by his life. My dad died a few years ago, but I’m still interested in how that system affects people’s lives. I know it did a lot of harm to him and my family. That’s where the New York part of it comes from. I feel a responsibility to uncover these stories so future generations don’t feel forced to work in that profession which can harm them and their family”.

When discussing the history of New York, which topics are you most passionate about teaching?

“A couple of ways of looking at that. One, I want to be as inclusive as possible. I want to be inclusive in that I want to present history in a way that’s not just about what rich white men did, which I think is not useful. Also, I trained as an environmentalist historian. I think that those prospects I found students to appreciate. They get interested in it, and many students realize there is a history they have not been exposed to. So, I think that that has been satisfying for me. When I introduce those topics, students seem more engaged than when I started teaching, and I would say, ‘Then this law was passed, and then this person was elected.’ I think inclusive and diverse topics, and those that are rooted in environment and health. Just looking at how people live their everyday lives, that people can relate to.”

The history of New York comes with lots of sensitivity. One of the most sensitive topics is racism. What important points do you consider when teaching students about the topic, considering its sensitivity?

“I think that you have to be willing to make people uncomfortable. And as a white person, I must be ready to make my fellow white people uncomfortable, and I’m eager to do that because white people have occupied the position of power in this country, and they still do for no good reason. That must be centered as a formative to the state’s development and to any society in the United States, to its development. When I started teaching, I was a little more nervous about it. How am I going to address this?

But now it’s just like this isn’t a matter of opinion; it’s a fact. I’ve gotten pushback and bad reviews from white students even. But I need to learn how to teach history any other way. If you don’t include that perspective, you’re being dishonest. I don’t know how people benefit from history; that’s dishonest”.

You do lots of environmental work. What initiated your interest in taking care of your environment?

“A couple of things. Childhood, growing up where I grew up. I was spending a lot of time outdoors. That played a role, living in that part of New York where there is so much conserved and preserved parkland and wildlife. Those places helped my mental health as a child. Those places were extremely helpful to me and just brought me peace and calm. And, when I was applying to graduate schools, that was the topic that interested me when I was an undergraduate. I read the first of environmental history when I was 19, and I loved the book, and I wanted to learn more. And so, when I was applying to graduate programs, I was focused on that. I chose Stony Brook because the atmosphere was relaxed there. Everyone there was supportive. So that’s the personal and then the professional interests combined”.

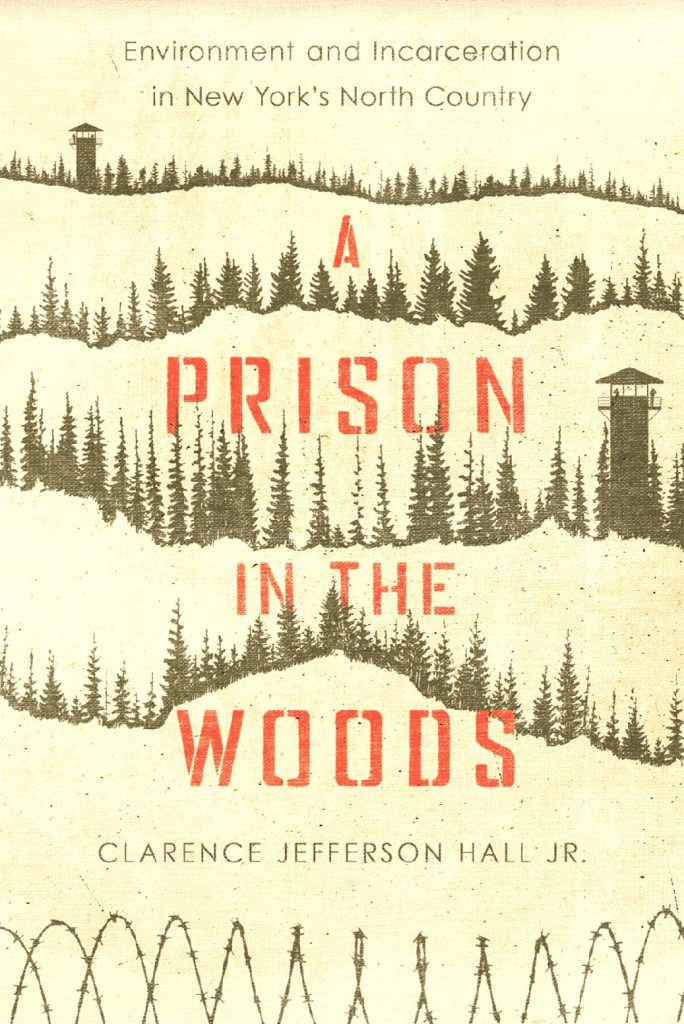

You are a published author, and your book, A Prison in The Woods, is based on the investigative work you have done on the correctional facilities in the Adirondacks in upstate New York. How is this topic, and the book itself, an essential aspect of your work?

“That was my doctoral dissertation, a big project I wrote for my Ph.D. The book is a complete rewrite of the dissertation, which took me a couple of years. It is the jumping-off point for my next project. My next project, my next book, will be about the town my dad grew up in. And so that town was the subject of chapter one of my book, but I only worked in the first 20 years or so of that prison, and there’s a century left to look at. This book’s focus will be the history of mental health, mental health trauma, and incarceration. I am working with Cambridge university press to get that published. My goal is to win the Pulitzer Prize for History. When you set a goal, set the highest goal. I am going to write a Pulitzer Prize-winning book. If you want me to order it [the book], I could give you a 40% discount and free shipping, authors discount. All the local bookstores in the Adirondacks carry the book. Or you can get it directly from the publisher if anyone wants it; I have a discount code. I am writing it because I love research and writing, and it keeps me connected to my family. Family history teaches me why I am the way I am. Without that, you have nothing to hold on to”.

How would you encourage your students to be more active in caring for the world and the people around them?

“Something that I’ve done that was very satisfying, that I hope I have more to do again in the future…volunteer for the people that have less than you. Find an organization or an individual and give your time. Some groups need people’s time and care. Just find something you care about, a group or a person, and give them your time”.

What are the best ways for students who wish to get involved in environmental work to do so both on and off campus?

“There is a student club (Environmental Sustainability Club) on campus. You can join that club and get involved in that group. Off-campus, volunteer. Every year on earth day, April 27, there are clean-ups in different neighborhoods that you can sign up for. Go and help clean up your community. You can volunteer with environmental groups working to combat climate change, pollution, and other environmental and public health problems. Just give it your time. If you care about it enough, give it your time. And if you know something, share it with other people. Use your social media”.

What is the biggest and most important lesson your work, both as a teacher and an environmentalist, has taught you so far?

“Two things, I think. One, never lose your curiosity. Do not stop learning. Do not close yourself off. Stay curious. Do not make your whole life about you and your social media feed. Engage with the world that you’re living in and be curious about it. You do not know what kind of doors can open for you. If you have a weird idea, go for it. Pursue it, and it will go somewhere. The other thing is do not isolate yourself. Engage with your community, with your family and friends. Contribute something. Think about your legacy, even now. How will people remember you? What kind of a reputation am I creating for myself? How will people discuss me, whether outside my presence, what will they say? Think about those things. That matters a lot. Those two lessons have stuck with me, stay curious and try to make a mark”.

For more information about Clarence Jefferson (Jeff) Hall Jr., visit the Queensborough Community College page or his website at cjeffersonhall.com or you you can send an email to jeffersonhall@gmail.com or CHall@qcc.cuny.edu.