By Olivia Corona

Public schools in the United States are no strangers to banning books— school board members across the country have listened in on many hearings from concerned parents and citizens over content perceived as inappropriate. Historically, books have been challenged because of the use of profanity and excessive racial and sexual tones. Classics such as Catcher in the Rye and Of Mice and Men have been questioned by communities as far back as 1950 for the author’s derogatory attitudes toward marginalized people and the sexual themes presented in both books.

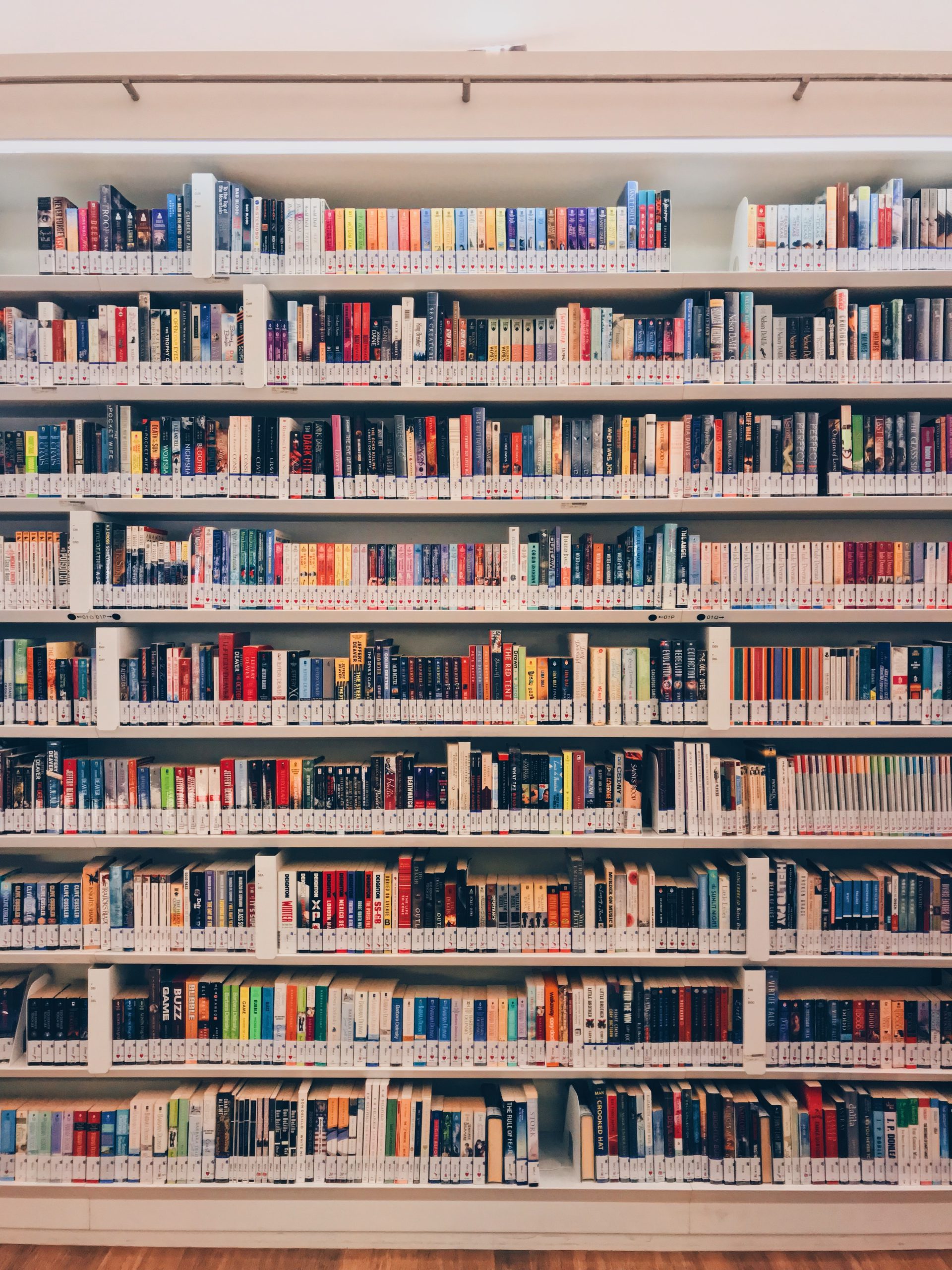

In the last few school years, there has been an rise in controlling students’ curriculum and along with what literature they consume. Pen America collects and creates an index of banned books in schools, and their findings for the 2021 to 2022 school year are an estimated total of 2,532 books banned from public schools. From the same data Pen America collected, they found that 41% of these books include a protagonist or secondary character who is a part of the LGBTQ+ community. Of the banned books, an additional 40% of titles contained protagonists and secondary characters who were of color, while the remaining 21% contained sexual content or sexual education.

Supporters of banned books are mainly parents and other local community members. However, they are backed by local, state, and national groups. Texas, Florida, and Pennsylvania are some states with the highest rate of book bans. It is becoming obvious that there is an effort to control the educational experience students are getting in America. The book ban has become a social movement that local and state governments support. One of the most outspoken proponents of book banning is Ron DeSantis, governor of Florida. DeSantis has gone as far as approving bills in Florida that limit how teachers talk about race, sexual orientation, and sex education. DeSantis says, “Parents want education for their kids: They are not interested in indoctrination through the school system.†DeSantis and like-minded supporters believe they are protecting parental rights, they think schools should not teach children about race, sexual orientation, or gender.

Instead, these groups want these conversations left to parents to decide what they teach their children, if anything at all. Momentum from this movement has gained so much attention that it is not just Florida anymore. Texas recently passed House Bill 900, which seeks to remove sexually explicit books off school shelves, and similar bills have been proposed in Kansas, Tennessee, Nebraska, and Oklahoma. Removing overtly sexual literature from schools is not the issue, the problem is that these states and local governments cite books like Gender Queer: A Memoir about the author’s personal experience with gender and identity. Governor of Texas Greg Abbott called the memoir “pornography,†while the memoir details the acceptance of pronouns and some discussion of sexual content as well as hormone-blocking drugs. Writings such as Gender Queer: A Memoir are essential for students, especially when teachers are unable to structure lessons on gender identity. Who Was, is another popular book, a biography about Supreme court justice Sonia Sotomayor and is now banned in Pennsylvania’s Central York school district along with other books that deal with civil rights and the history of racism in America.

The debate here seems to be with diversity and acceptance, one in five people who are Generation Z and one in ten millennials identify as a part of the LGBTQ+ community and countless people of color. Restricting what types of conversations teachers have in schools and censoring what content students consume is not only harmful but dangerous. The first amendment protects students, they have a right to access information and ideas even if that information is outside their parents’ and communities’ worldviews.